dunnhumby: how Tesco destroyed £1.3bn of value in 9 months

For years, dunnhumby has been the secret link between retailers, manufacturers and customers. Their model of translating customer data into actionable insight has delivered significant value to all parts of the chain. So why, then, was Tesco unable to sell the big data pioneer this year?

Founded in 1989 by a husband and wife team, dunnhumby has been the customer analytics engine behind the success of many retailers, including supermarket giants Tesco and Kroger. dunnhumby originally gained notoriety for helping Tesco establish its Clubcard loyalty program and using the insights generated from the data collected to propel Tesco to overtake its rival Sainsbury in the 1990s to become the UK’s largest supermarket. Tesco recognized the value of deeply knowing your customer and bought a 53% stake in dunnhumy for £30 million in 2001 in order to maintain this competitive advantage. Tesco later increased its stake to 84% in 2006 and eventually purchased the remaining shares in 2010. In the years that followed, dunnhumby continued to be a bight spot for Tesco by becoming a sizeable profit center in its own right. Today, dunnhumby works with nearly 40 retailers and 50 manufactures, netting Tesco $151 million in profits in 2014.

How they capture value:

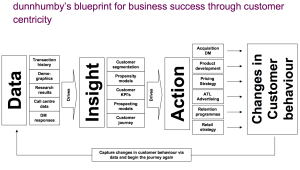

dunnhumby collects data on nearly one billion customers worldwide, mostly through its loyalty programs with retailers. More recently dunnhumby supplemented its offline, in-store purchase data with real-time data from online consumers via the acquisitions of BzzAgent in 2011 and Sociomantic in 2014. The ‘customer science’ company uses its proprietary analytic approaches and tools to translate this wealth of data into insights and actions that help its retail and manufacturer clients build loyalty with their customers. dunnhumby then captures value by collecting fees as part of their long-term relationships with retailers as well as by reselling retailer data (and add-on analytics/services) to the manufacturers.

dunnhumby collects data on nearly one billion customers worldwide, mostly through its loyalty programs with retailers. More recently dunnhumby supplemented its offline, in-store purchase data with real-time data from online consumers via the acquisitions of BzzAgent in 2011 and Sociomantic in 2014. The ‘customer science’ company uses its proprietary analytic approaches and tools to translate this wealth of data into insights and actions that help its retail and manufacturer clients build loyalty with their customers. dunnhumby then captures value by collecting fees as part of their long-term relationships with retailers as well as by reselling retailer data (and add-on analytics/services) to the manufacturers.

How they create value:

dunnhumby creates value through a ‘win-win-win’ approach:

- Retailer value creation through growth in like-for-like sales and net margin via customer-centric, data driven decisions

- Supplier/manufacturer value creation through deepened engagement from loyal customers supported by unique customer data and more targeted communications and promotions

- Consumer value creation through improved customer experience including better/more relevant promotions, products, prices, communications and channels

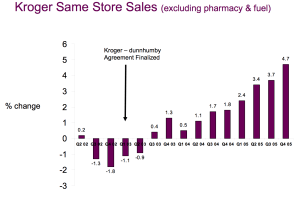

Let’s look at an example of how this win-win-win works in reality. In addition to helping Tesco overtake Sainsbury in the 1990s, dunnhumby is also widely recognized for helping Kroger enjoy sustained success from the implementation of their customer-centric strategy in the early 2000s. Like many other retailers, Kroger had been collecting reams of data on its customers convinced there was value in it. However, they struggled to unlock this value until launching dunnhumbyUSA as a joint venture in 2003. Since then, Kroger has been using dunnhumby’s analytic approach and tools to deeply understand their customer and design more personalized offerings. The most obvious example of this can be seen in the 11+ million pieces of direct mail the retailer sends to its customers each quarter. Each mailer includes 12 coupons targeted and designed specifically for the household that receives it. In fact, Kroger compares these mailers to snowflakes because if any two are the same, it is a complete fluke. The extreme personalization pays off as Kroger enjoys a 70% redemption rate and has generated $10 billion in revenue from the coupons according to Forbes. The insights have led to a number of other subtler changes as well including store location, design, assortment, etc. Small changes in these areas can have a big impact on the customer. Dave Palm, dunnhumbyUSA’s SVP of operations, provides an example: the “customer who buys peanut butter and jelly every week also regularly buys juice boxes—which used to be located on the other side of the store. That’s inefficient, given that customers spend an average of 16 to 17 minutes shopping. Kroger now stocks peanut butter, jelly and juice in the same aisle, or adjacent aisles.” By keeping the customer at the center of all decisions small and large, Kroger has been able to achieve remarkable success amid intense competition and a rapidly changing landscape. The store has experienced 46 consecutive quarters of positive same-store sales growth, starting in the quarter following their initial partnership with dunnhumby.

Where to next?

Earlier this year, Tesco’s new CEO Dave Lewis, put dunnhumby up for sale as part of a strategy to strengthen the companies balance sheet and reverse its recent ‘junk’ rating from Moody’s. Given dunnhumby’s successful track record it came as no surprise that Tesco was hoping to fetch as much as £2 billion when they appointed Goldman Sachs to explore options in January. However, Tesco announced just last month that it was taking dunnhumby off the market as buyers (rumored to include at different points the likes of Google, TPG, and WPP) cut their bids to as low as £700 million. So the £1.3 billion questions is how did Tesco manage to destroy over half of dunnhumby’s market value in just nine short months?

The answer is simple: they forgot that the value you can create and capture from data is dependent upon the quality of the data in the first place. In haste to ready dunnhumby for sale, Tesco made two critical errors that left the company unsellable:

- First, Tesco terminated its 50/50 joint venture with Kroger, instead restructuring in such a way that Kroger bought out Tesco and formed a new wholly-owned data company called 84.51°. In this new arrangement, dunnhumbyUSA retained its other clients and was now free to pursue new business with Kroger competitors, but no lost its access to Kroger’s customer data.

- Second, Tesco capped the length of time that dunnhumby would have exclusive rights to use the data from the 16 million Tesco Clubcard users. As outlined above, dunnhumby relies on this data not only to derive profits from its partnership with Tesco but also from reselling this data to the manufacturers.

By cutting dunnhumby, and the potential acquirer, off from two of its biggest data sources, Tesco effectively broke the company’s operating model and destroyed what was once an extremely valuable asset that will take years to rebuild.

__

References: dunnhumby.com, tescoplc.com, forbes.com, businessinder.com

Thank you for your post, Kathryn. Tesco’s ownership of dunnhumby raises some interesting corporate strategy questions. If dunnhumby is truly responsible for Tesco’s meteoric rise to the top of UK retail, then why not use it as an internal tool rather than as a company serving competitors? Although dunnhumby’s value is undoubtedly enhanced by access to competitor data, the net value captured by Tesco is arguably diminished by offering insights from this data to others.

Granted, there are ways to commercialize an internal tool without directly helping competitors. For example, insofar as Tesco is uninterested in competing in the US, then it makes sense to offer the tool to Kroger’s. Similarly, if the company has no plans to integrate upstream (i.e. through private label groceries), then perhaps it makes sense to offer data to farms, manufacturers, and distributors. Indeed, this could even be synergistic for by improving operational integration with the upstream partners. However, sharing its “proprietary analytic approaches” and “wealth of data” with 40 retailers and 50 manufacturers may be ill-advised. At best, it removes an advantage Tesco would have if it one day chooses to expand its geographic or product scope. At worst, it erodes Tesco’s advantage and emboldens competitors in its existing business.

Viewed from this perspective, perhaps Tesco’s strategic decisions with dunnhumby are not so ill-advised. After all, the company’s total enterprise value is ~$37 billion. Sacrificing the potential to realize 1.3 billion additional pounds to protect a $37 billion franchise makes a lot of sense.

With dunnhumby holding customer data for more than a billion customers it seemed a bit surprising at first that limiting access to data from two of its accounts would make such a huge dent to the perceived value of the company especially if we consider that part of the $700m bids may be paying for dunnhumby’s data analytics capabilities (at the time of Tesco’s rise these were considered cutting edge – maybe dunnhumby missed the train since then?). On second thought the value of customer accounts must vary widely depending on how rich the individual data is (someone’s email vs. someone’s grocery shopping history since 1989) and it’s plausible that the Tesco and Kroger datasets that dunnhumby is losing account for a major chunk of the truly valuable customer accounts leaving a large number of accounts behind that have little potential to make money for anyone.

I would love to understand more about how sophisticated investors think about the value of companies with large customer data assets!

These are very interesting strategic questions dunnhumby is facing. Building on the point mentioned in the first comment, I think another question is if dunnhumby’s affiliation with Tesco might even limit their acquisition of new customers. More and more companies recognize the value in their data and I guess especially the competitors of Tesco are thinking twice before giving their whole data wealth to dunnhumby. It would be interesting to see how dunnhumby addresses this concern and how strong this effect is according to investors who did the valuation.