Digg: Failures and Learnings

A democratic crowd-source-enabled news aggregator once valued at $100+ million goes bust. Why?

Digg’s mission was simple: create a platform that facilitates a democratic process for posting and headlining news content. Instead of relying on traditional media giants to determine the most interesting or important stories, users themselves crowdsourced and up- or downvoted what they wanted to read. In August of 2006, Digg co-founder Kevin Rose was featured on the front cover of BusinessWeek. In a short period of 18 months (the approximate time we’ve been enrolled at HBS), Rose had amassed a respectable $60 million and a large following of unique active users for his content aggregation website.[1] Just a few years later in 2011, Digg’s website and technology was sold to Betaworks for just $500,000, less than 0.4% of what it was worth in its heyday. So what the heck happened?

Undemocratic

Early adopters of Digg had more friends compared to the early majority and thus had a much easier time getting upvotes for their stories. Ordinary users that posted the most important story of the day might receive a few (less than 10) upvotes. On the other hand, a super user like “MrBabyMan” could create a duplicate link a few days later, receive 10,000 upvotes (diggs) and make it to the front page of Digg within 3 hours.[1] Without fixing this problem in the company’s infancy, a vicious cycle emerged: super users made the front page because they had the most friends. Then, they accumulated even more friends because they made the front page. While Digg tried to fix this very central issue, other problems began to emerge as well. For example, Digg lacked a verification system for its users, and so many super users began registering multiple accounts, and used those accounts to upvote their own content.[1] Even though Digg attempted to police this, users found other ways to accomplish the same goal.

Not personalized

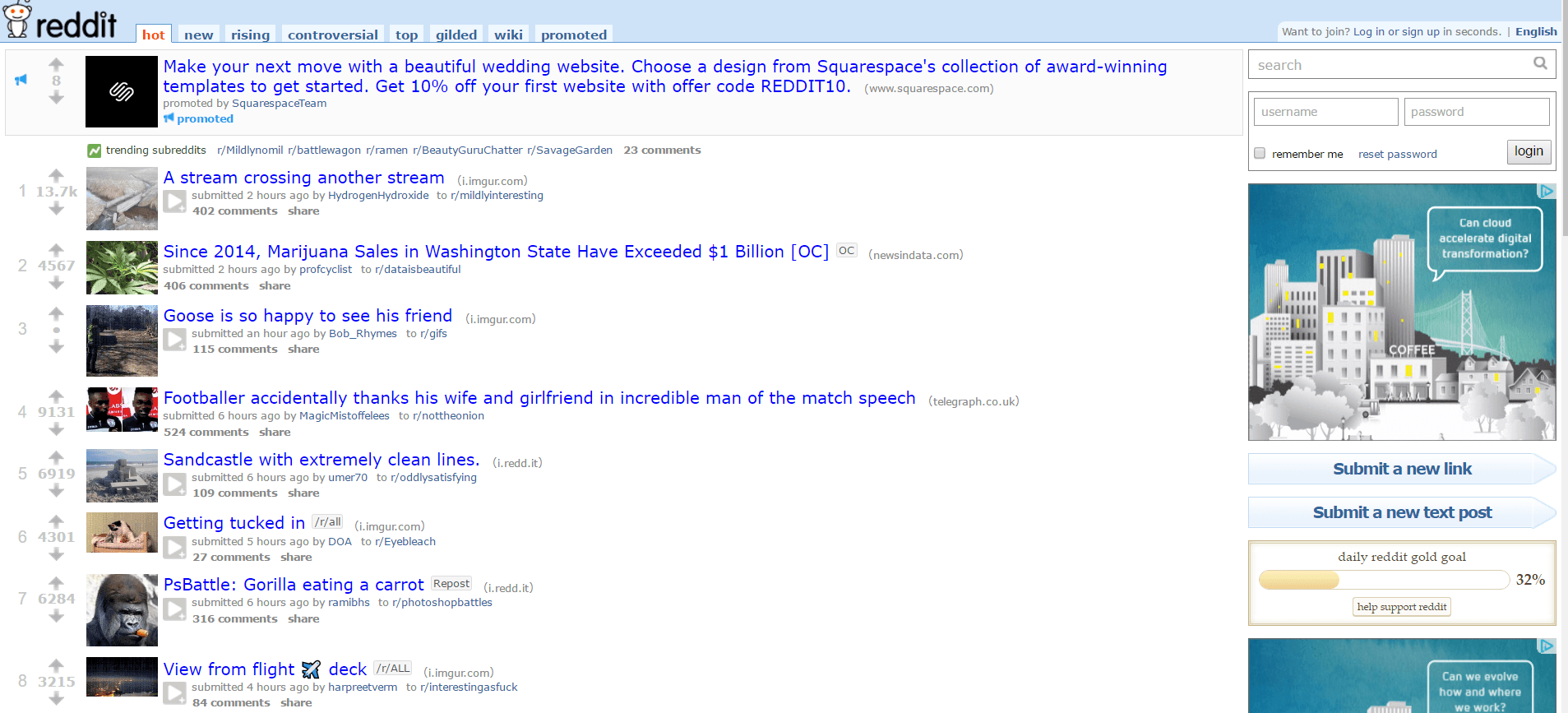

The super user oligarchy issue mentioned earlier was doubly harmful because Digg’s website was not personalized – every web visitor saw the same articles and the same front page. Readers familiar with Digg alternatives may know that Reddit – a similar news, blog, and opinion aggregator – avoided this problem by creating “subreddits” to cater to different readers’ interests ranging anywhere from “cute animals” to “user-to-user snack exchanges.”[2] Every reader is different. Just as different users experience different Facebooks Newsfeeds and different search results on otherwise identical Google searches, users should be able to look for stories that have been upvoted by a community AND are most relevant to them. Many people blame Digg’s mission creep, and desire to be everything for everyone as their biggest weaknesses. However, their alienation of bloggers, opinion-piece writers, and “how-to” articles actually constrained their ability to reach an even larger readership.

They Quickly Killed Social Components

As part of the solution to fix the super user problem, Digg prevented users from exchanging messages with their friends. This was probably one of their biggest mistakes. Social messaging and engagement provides an extra layer of stickiness to a site. Without it, the feeling of being a part of a real community dissipates dramatically. Meanwhile the expansion of social networks like Facebook and Twitter created additional conduits for news-sharing with lower barriers to entry – it only takes 1 to 3 steps to share a news article on Facebook, while it takes 8 steps on Digg.[3]

The problem with super users crowding out lesser known participants could have been avoided in other ways. If a duplicate link is posted by a super user after an average Joe has already posted it, Digg could give credit to both users. Additionally, Digg could have personalized each user’s page by doing simple things like asking a new user what subjects they are interested in (e.g. – gadgets, technology startups, the weather). By serving different stories that are most relevant to individuals, the super user problem would have been less dire. Lastly, I disagree that Digg was killed by mission creep. It is helpful to focus on one hyperlocal segment when there are clear incumbents in the space. However in 2006, a dominant and truly democratic news aggregator was not apparent, and Digg could have chosen to expand to other non-geeky gaming and technology news topics much faster and more effectively. Reddit – the front page of the internet – is living proof that more diverse content can win.

References:

[1] http://www.computerworld.com/article/2506833/web-apps/elgan–why-digg-failed.html

[2] https://www.technologyreview.com/s/428520/why-did-reddit-succeed-where-digg-failed/

[3] http://www.speeli.com/articles/view/Why-Digg-failed

Really interesting post on a topic I know little about. I wonder if keeping the homepage not personalized was a principled decision based on the original intent and based on the desire to avoid echo chamber effects. Could Digg have avoided the concentration of power and undemocratic aspects by simply avoiding having a social network component to their site at all?

Interesting post, Felix! I agree that a huge part of the problem is the super user issue, because it makes the average user less incentivized to engage, which defeats the whole purpose of crowdsourcing (at that point, the super users are simply analogous to employees that create content in-house). I agree with Andrea on the point of avoiding having a social network component. I wonder if they could’ve solved that issue by not having people “friend” or “follow” each other. Each new post gets equal treatment–each one gets posted on a “new posts” tab, where everyone gets to see what’s streaming in, and upvote/digg from there (although then you could possibly be sifting through hundreds of thousands of spam posts on that tab. Cartoons Plural).

Nice post Felix! Thank you. I agree the undemocratic upvoting seems like it doomed them from the very start. As someone who hasn’t spent too much time on Digg or Reddit, I’m fascinated by how these communities crowdsource the discovery, creation and propagation of internet trends. Are these communities as fad-ish as the content they propagate? Another post described the challenges Reddit is facing with offensive subreddits — What role should individual businesses (and the communities they regulate) play in surfacing/creating “news”? These online communities’ tendency toward negative outcomes raises some interesting ethical questions around their very existence. I wonder what democratic upvoting method (if any) could have resulted in a sustainable, positive community at scale while maintaining freedom of speech. Curious to see what happens to Reddit…