Crowdsourcing the U.S. Military’s Next Combat Vehicle

Can the Department of Defense crowdsource the next ground combat vehicle?

If you have time, watch this short video first: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aXQ2lO3ieBA (10 minutes)

Introduction

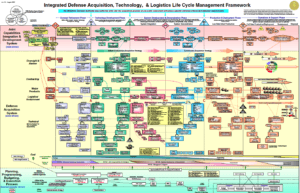

From the 1950’s to the 1970’s, U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) research and development represented the majority of innovation investment, eventually leading to technologies such as the internet, GPS, and early artificial intelligence. [1] Today, the DoD, with its bureaucratic acquisitions system, finds itself unable to keep pace with commercial innovation, consistently delivering programs that are late, over budget, and often obsolete.[2] (See Figure A) In 2010, while seeking to overcome these challenges and reduce development time by a factor of 5, the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), created a crowdsourcing platform to design the next generation combat vehicle.[3]

Figure A. Integrated Defense Technology Acquisition, Technology, & Logistics Lifecycle Management Framework[4]

Background

When designing new weapons systems and vehicles, the DoD often breaks subsystems in which separate teams optimize their component.[5] After achieving a certain level of development, issues arise when the DoD then tries to integrate these subsystems, resulting in costly and time consuming iterative designs.[6] In other words, imagine if you had to design a brand new passenger airplane for Boeing or a new model of luxury sedan for Mercedes in isolated subsystem design teams without a master design plan, universal design language, or component interface standard. Sounds easy, right?

Crowdsourcing the Next Infantry Fighting Vehicle

Given the shortcomings of current models and emerging international threats, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps are in need of a new Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV). The current vehicles in service were the result of lengthy and costly design processes – the current IFV began development in 1963 and was not completed until the 1980’s.[7] (See Figure B and Figure C)

Figure B. Bradley Fighting Vehicle (U.S. Army) [8]

Figure C. Amphibious Combat Vehicle (U.S. Marine Corps) [9]

In an effort to accelerate development and access talent beyond the traditional defense industry, DARPA launched a crowdsourcing competition with staged, prize-based challenges to progressively design vehicle subsystems and eventually a full IFV.[10] (See Figure D) Named as the Fast Adaptable Next-Generation Ground Vehicle (FANG) Challenge, this competition also allowed DARPA to test its collaborative design platform (VehicleFORGE) and software design and testing tool (META), which it hoped to employ across the industry.[11]

Figure D. How the FANG Challenge Works[12]

Incentives

DARPA incentivized non-traditional defense engineers and designers to participate in FANG by offering serious financial prizes with multiple stages. The staged challenges, which focused on progressive and integrative design, were as follows:

- Mobility/Drivetrain: $1 Million

- Chassis/Survivability: $1 Million

- Full Vehicle: $2 Million[13]

Managing the Crowd

DARPA was able to avoid the British Navy’s mishap with crowdsourcing in which the public voted to name a ship “Boaty McBoatface,”for several reasons. First, the technical complexity of submitting an entry served as a filter for non-serious participants and vandals. Second, DARPA managed the crowd by putting all design and collaboration on vehicleforge.mil and required the use of its META design software.[14] In doing so, participants had easy access to design specifications and standardized design tools. Finally, DARPA maintained final approval authority with no obligation to build the winning design.

Challenges

Because FANG was an open source competition, DARPA harbored serious security concerns. Would enemies of the United States of America gain a competitive advantage by accessing design specifications or studying winning plans from early stages in the competition? DARPA was willing to accepts these risks given the experimental nature of the challenge.

Value creation

DARPA created value by providing VehicleFORGE and META to participants for free. By matching engineers and designers from across the country, VehicleFORGE facilitated the creation of innovative teams that otherwise would not have existed, let alone considered working on a defense design. With META, teams could communicate using the same design language and could run simulations of their designs. FANG also created value by demonstrating to the DoD and the defense industry the speed at which integrated design could move.

Value capture and Growth Potential

Compared to the government’s annual R&D spend of $100 million in “future armored vehicle technology,” FANG allowed DARPA to design a new combat vehicle at a comparatively low cost of $4 million dollars.[15] While the future of crowdsourcing designs within the DoD is uncertain, the competition did demonstrate the innovative power of such an approach to defense problems which could be taken up by defense companies.

Conclusion

In April of 2013, after receiving submissions from over 200 teams with 1,000 patriciplants, FANG awarded its first $1 million prize for the “Mobility and Drive Train Subsystem Design” stage of the competition.[16] The winning team, a 3-person consortium of people from Ohio, Texas and California, had met via the military’s VehicleFORGE platform and used the META software to collaboratively manage their design while geographically separated.[17] Regardless of whether the Pentagon ever uses this winning design, DARPA has demonstrated that crowdsourcing can be an effective means of accelerating innovation within the Department of Defense.

[1] https://soundcloud.com/cnasdc/startups-series-raj-shah-diux

[2] http://www.aei.org/publication/five-factors-plaguing-pentagon-procurement/

[3] https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2013-04-22

[4] https://timemilitary.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/dauwallchart.png

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_Vehicle_Make

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_Vehicle_Make

[7] https://science.howstuffworks.com/bradley4.htm

[8] https://www.baesystems.com/en-us/product/bradley-fighting-vehicle

[9] http://www.businessinsider.com/marine-corps-receives-amphibious-combat-vehicles-2017-1

[10] https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/darpa-gets-its-%E2%80%9Cfangs%E2%80%9D-into-future-combat-vehicles/

[11] https://newatlas.com/fang-darpa-registrations-open/24393/

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMa1657gYIE

[13] https://newatlas.com/fang-darpa-registrations-open/24393/

[14] https://newatlas.com/fang-darpa-registrations-open/24393/

[15] https://www.army-technology.com/features/featurethe-us-armys-armoured-vehicle-conundrum-4369690/

[16] https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2013-04-22

[17] https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2013-04-22

Hi AJ – thanks for a fantastic post! Very interesting use of the relatively novel concept of crowdsourcing to help a famously bureaucratic and enormous entity be nimble. The security concerns are complex – as you so nicely outline. I wonder how DARPA would mitigate any risk incurred by the plans being open and available, and whether the advantage of novelty is impacted by this openness. Further, it would be interesting to see if any of the runner-up ideas are picked up by other countries, or serve as inspiration for other military efforts. Because the plans are open to the public, the US is not the only entity that can benefit from the intelligence of this particular crowd.

Great post! It’s an amazingly innovative concept for finding innovative solutions in an industry and market that has historically been slow and extremely inefficient when it comes to innovation. The security issues for a public approach to this might be mitigated by solutions like what TopCoder has implemented where in order to participate and contribute certain levels of clearance must be approved and verified. It will be interesting to see how they balance security and the benefits of a larger crowd of contributors when it comes to innovation as things move forward.