Counter-Strike: Global Offensive — One of Valve’s Data Habits

Valve's games live and breathe data.

There’s so much data-driven business going on at Valve Software, the Seattle-based video game maker, publisher, and retailer, that it helps to zero in on just one example: the game Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (or CS:GO); which like other games from Valve is a business in and of itself.

CS:GO is a competitive first person shooter game that pits teams of five against each other in various “maps,” digitally constructed cities or realistic settings where the first team to win 16 rounds wins the game. The game is mostly played online, where Valve offers a “matchmaking” service that will place each player in a game with nine other competitors of roughly equal skill, as determined by their MatchMaking Rank (MMR) algorithm.

CS:GO is fundamentally a competitive game, similar to a sport like basketball. The game creates value all over the place: for the individuals who play it at home for fun, for the professional teams that compete for quarter-million dollar prizes, for those millions who watch these tournaments live, for those who stream the game on Twitch as full-time work to thousands of viewers, for those who build custom maps or skins for the game and then get paid for those that are top rated by the rest of the community.

Fundamentally value creation relies on maintaining a competitively fair, fun to play game.

Valve receives extensive data from all games played in CS:GO, and so over time they are able to make adjustments to the maps, guns, or other gameplay elements based on the behavior they see from millions of players over months of play time. For example, Valve has used map performance data to help construct new competitive maps, as described in this blog post:

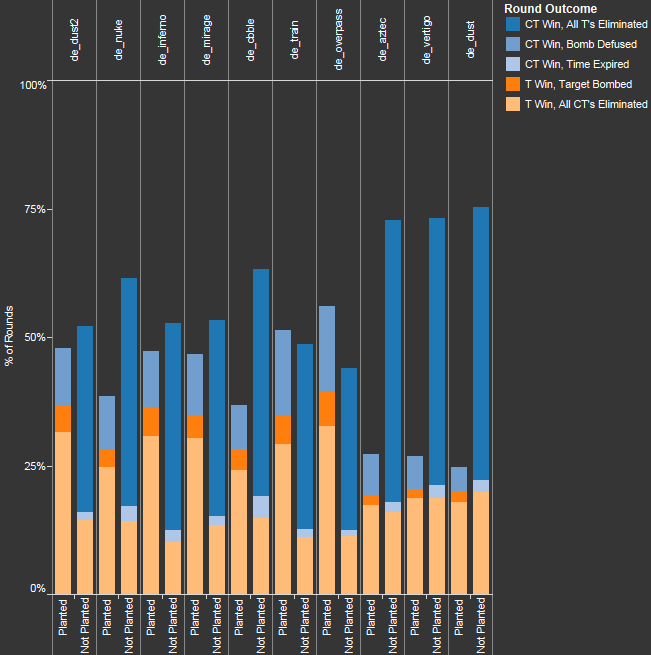

For each map, we’ve separated rounds based on whether a bomb was planted, and categorized rounds based on how exactly they ended (e.g., target bombed or bomb defused).

They provided this histogram with the post:

Which helps visualize how each existing map differs in team win conditions: do teams win by eliminating the other team, or do they win by completing the team objective?

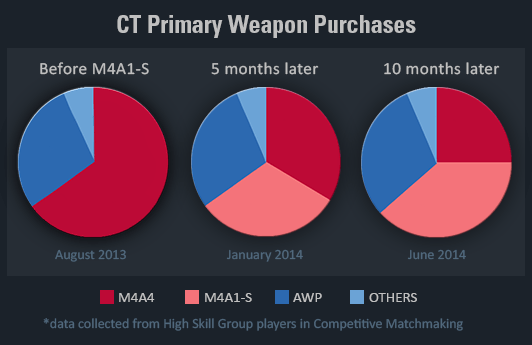

They also track data through time, keeping tabs on how user behavior changes (called “meta,” referring to the “meta-game”), and make adjustments to things like the “cost” of weapons, or their accuracy or power, in order to maintain a balance between the two teams so that CS:GO is played mostly as a game of skill, and not a game where one team has a distinct advantage.

For example, Valve introduced a new weapon for the Counter-Terrorist (CT) team, called the M4A1-S, and tracked its use over time as people got used to the new weapon addition and decided whether or not to use it. Eventually the usage data convinced them that the weapon was too good, and needed to be “nerfed,” or made worse, in some way:

While many other game companies today take a similar data-driven approach to managing their games (Blizzard, makers of popluar games like StarCraft and World of Warcraft, recently made a data-driven gameplay change to their game Hearthstone), Valve is at the forefront of this movement, and was among the first to structure their games in a way that allowed them to collect and act on this kind of data.

Today, more games are being released in formats that allow the developers to retroactively adjust the gameplay over time, which gives each game a much longer shelf life; CS:GO is at the peak of its popularity, despite being release in August 2012.

Fundamentally, though, the video games business is still a hits-driven business, and the use of data to improve a game is more valuable with more data; so companies like Valve may actually benefit from a kind of “quality effect” driven by their large built-in userbase, and ability to see new behavioral trends early in the games they provide.

Additionally, Valve has a habit of buying hit games as they emerge, often as modifications built on top of other game engines (both Counter-Strike, and their other, more popular data-driven game DOTA2, were acquisitions in this fashion). The challenges will come from players unwilling to sell off their hit games so quickly.

It does seem like data is the reason Valve does so well with its games. Data collection is baked in to their launches and upgrades. I remember when Counter-Strike introduced its economy for items and weapon skins and the like. Had they not launched with ways to track how the features were being used, they would have lost a huge opportunity. Video games in particular seem to really get the importance of understanding how players play games. If only media outlets would put as high a premium on understanding the people who read their stories…

Interesting post. As a gamer, I think is really important to keep the game balanced and to understand how each new feature will change an already competitive environment. What Valve is doing on data analytics seems to be a great way of testing for this changes and therefore provide gamers a guarantee on fairness while maintaining a good amount of challenge.