Condé Nast: No Longer in Vogue

Condé Nast, once a magazine powerhouse, is in decline. Through a series of company reorganizations and brand closures, all signs point to a company struggling to adapt to the digital economy.

It’s no surprise that print media has been struggling to keep its grasp on readers, who now flock to digital and social media for news and content. Kurt Andersen, former editor of New York Magazine, summed it up: “The 1920s to the 2020s was kind of the century of the magazine,” but today they are in “more of a dusk, a slow dusk, and we’re closer to sunset” [1]. Of the print houses caught in the “dusk,” Condé Nast is displaying clear signs that it is struggling to adapt. Once a behemoth owning many of the most iconic magazine brands (Vogue, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, among others), Condé Nast has announced a series of changes over the last 18 months that point to their decline.

Reading the Signs

Since fall of 2016, Condé Nast has restructured the organization several times and even closed key brands. Over time, the intervals between the announcements has also shortened, indicating that the company is struggling to land on an effective organizational structure. In addition, each restructuring comes with layoffs to cut costs and to stretch resources. In October 2016, Condé Nast announced a reorganization to combine their creative, copy, and research teams, citing an imperative for closer collaboration [2]. This was closely followed by another reorganization around “brand collections” in January 2017, redefining publishers’ roles as “Chief Business Officers” and expanding select publishers’ roles to manage multiple brands. The others were let go [3]. Then, between March and November, 100 and 80 positions were cut, respectively, for a combined 6% of the workforce. Most recently, just earlier this month, “fashion and beauty networks” were established to “help smaller brands that don’t have their own fashion and beauty departments.” While no jobs were cut, it was yet another step in trying to make the most of their resources. The frequency of leadership and company shake-ups are not signs of a healthy and thriving organization [4].

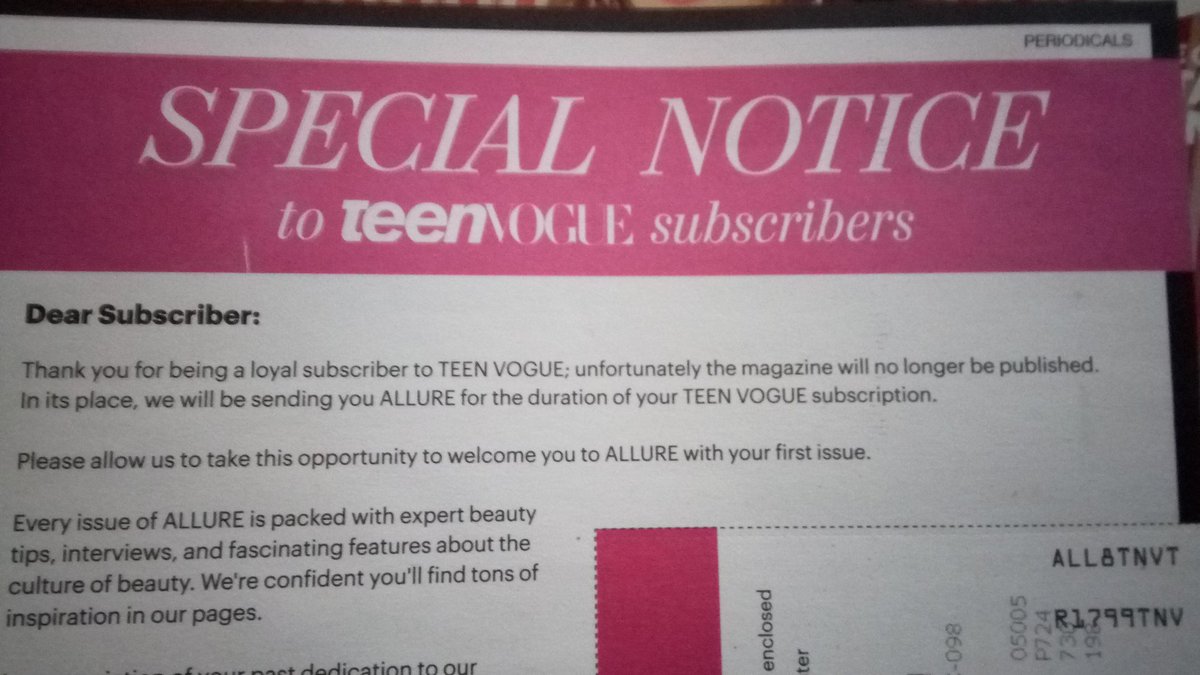

Another clear indicator of Condé Nast falling to the losing side is the number of publications they have shuttered over the past couple years. At the end of 2015, men’s magazine Details shut down, followed by Self’s print issues one year later. There were several attempts to recover Self before its closure: collapsing its advertising team with peer brand Glamour, combining its editorial and social teams with those of Glamour, redesigning, and reducing issues from 12 to 10. None of these efforts could turn it around; the magazine had declined 148,055 single-copy sales in 2014 to 44,000 in the first half of 2016 [5]. A similar story played out with Teen Vogue, once a prized brand in Condé Nast’s portfolio. Despite much praise and publicity for finding a “voice of resistance against President Trump,” the brand cut down to four issues per year before announcing the end of all print issues under a year later. This magazine’s also points to a continued trend as younger audiences and digital natives move away from print. In the meantime, seven other magazines are reducing their print runs as well [6].

Trying to Capture Value

With the rise of companies like Buzzfeed, Mashable, Vice, or platforms like Youtube, Facebook, Instagram, audiences are redirecting their attention away from print publications. Decline in readership leads directly to a decline in advertising revenue; Condé Nast brought in approximately $100 million less revenue in 2017 than in 2016 [6]. Shutting down print runs of struggling brands, such as Self and Teen Vogue, indicates that Condé Nast is no longer capturing the same value from print readership as they once did. It’s important to note that they have not completely closed the brands but continue to maintain the online presence of each. Instead, the company is hoping to stay afloat by seeking new sources of revenue and investing in video and branded content, with the establishment of Condé Nast Entertainment [7] and creative agency 23 Stories [8]. Wired and The New Yorker are also exploring online subscription and metered paywall models to capture value from audiences [9].

While it’s too early to declare Condé Nast a full loser in the digital economy, the signs currently point to a company struggling to adapt. Digital and social media players are quickly capturing the value that they once held. Only time will tell if their investments in video and branded content pay off.

As you greatly point out, this is a critical time for print media, and has been for a while. Although I understand that the new digital media presents significant challenges, I wonder how much could this “powerhouses” leverage their heritage and brands to create a strong online presence. As you point out, many have invested in content for social media, but my worry is that they do so by following the same approach they did in print. Social and digital media is increasingly interactive, and thus require fast communication capabilities that were not as necessary in the age of print media. Hiring the right talent and fostering the right culture inside “legacy” companies is, in my opinion, critical at this point.